The theory of scintillation is about electromagnetic wave propagation in structured media. But why does a phenomenon that has been studied for nearly a century now merit a new theoretical expose? One part of the answer is that the essential elements of the standard theory are too easily comprehended.

https://chuckrino.com/?p=36

Consider the random lens model mentioned in my earlier post. That conceptual picture is not far removed from the standard textbook development of the theory, for example the development of imaging through turbulence in Chapter 8 of Statistical Optics by Joseph Goodman. The theory provides an explicit representation of wavefront phase, which is very appealing for optical system analyses. Nonetheless, any theory that builds on a mathematical separation of amplitude and phase cannot be reconciled with the recognized theoretical developments that have evolved over the past 30 years because they address complex field moments. Conversely, that comprehensive theory (summarized in Chapter 3 of my book) provides very little utility for solving practical problems.

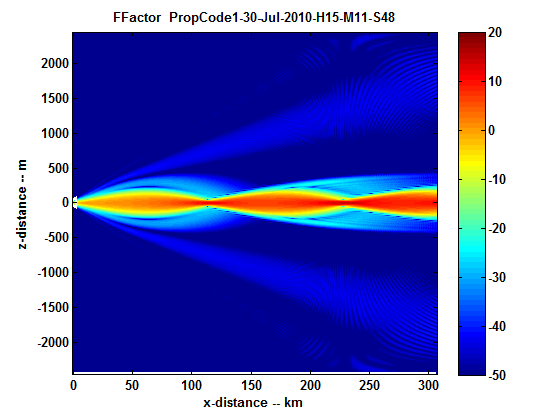

The resolution of the dilemma and the compelling reason for revisiting scintillation theory comes from the computer revolution. Although the idea is not new, the complete theory of wave propagation in structured media is encapsulated in a comparatively simple first-order differential equation. The equation admits robust integration using a well-known algorithm that is easily implemented and executed with inexpensive personal computers. The development is facilitated by interactive languages such as MATLAB. Thus, simulations based on very high fidelity models bridge the gap between theoretical results that are either over-simplified or unwieldy. With such simulations one can also explore the combined effects of path-loss, wavefront curvature, and antenna effects.

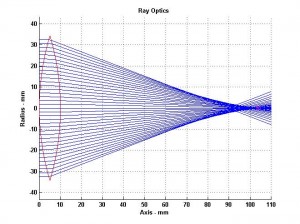

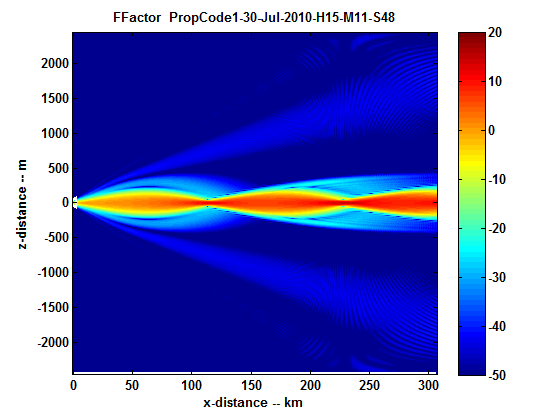

An example from Chapter 2 of my book (shown in the Figure above) simulates beam propagation along a layer with increasing inward radial refractivity. As the beam expands, refraction redirects the energy toward the axis where a local focus functions like a local source.

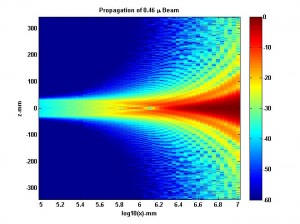

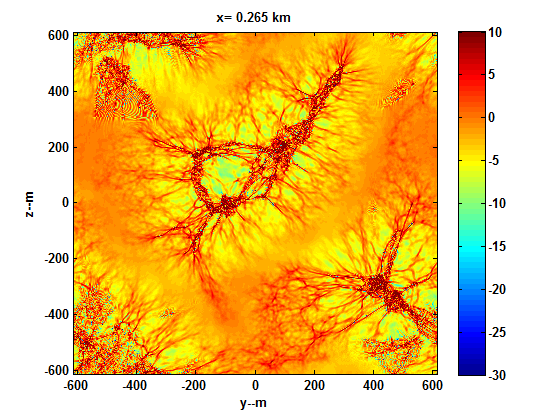

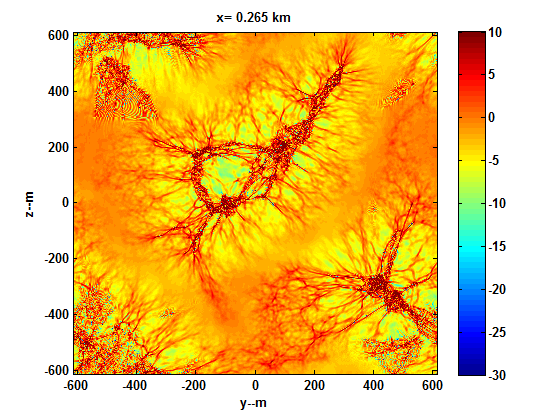

A second example, which has already been introduced, is strong focusing. The image shows fine intensity detail that admits no meaningful continuous phase reconstruction. Yet, back propagation can be used to fully reconstruct the disturbance at the edge of the disturbed region.

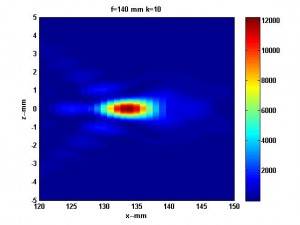

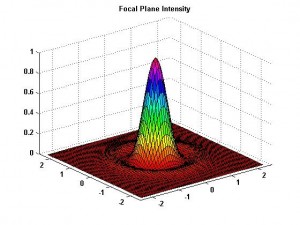

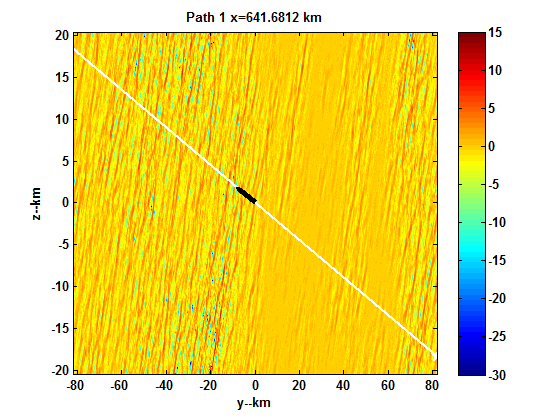

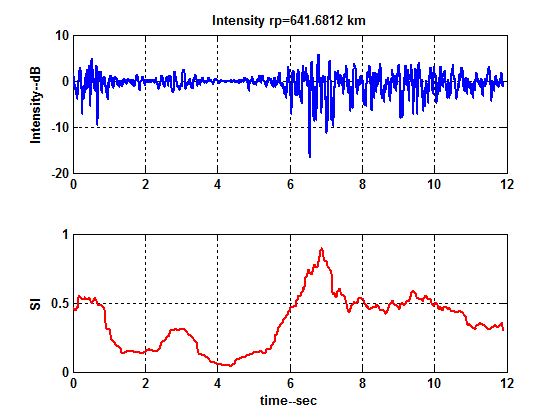

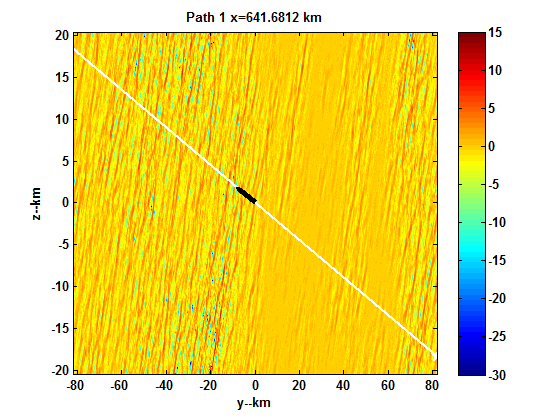

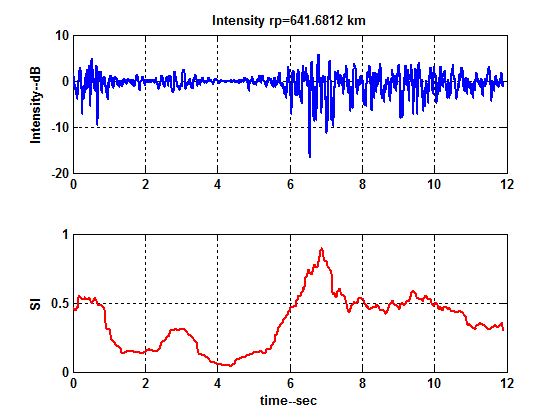

A third example shows the same type of simulation for propagation through highly anisotropic media at oblique incidence. The overlaid white line and arrow show the apparent scan direction induced by source motion. The final figure shows the intensity and reconstructed phase along the scan direction, which is what a Beacon satellite receiver would observe, ideally.

A directory of MATLAB codes with scripts that will reproduce all the examples in the book and more will be available for download on the MATLAB Central website.